Students prepare for the complexity of energy transition

Posted on

Future Energy Systems students Miles Skinner, Andrea Miller, Sonak Patel, Janina Fuchs, and Natalia Vergara Bonilla.

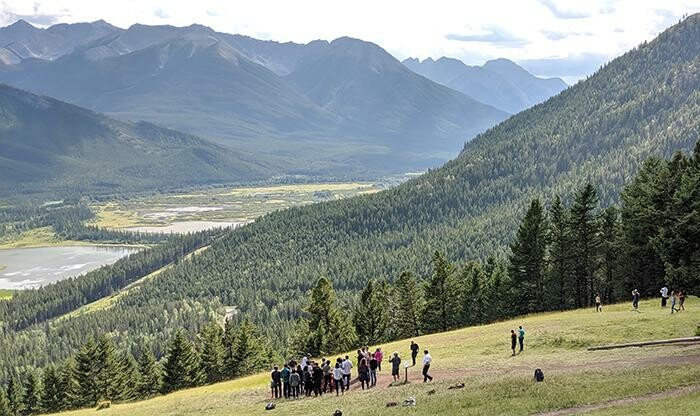

Future Energy Systems students join international counterparts at ABBY-Net summer school to develop interdisciplinary energy transition solutions

Miles Skinner likes to tell people how hard the energy transition will be.

“Look at cement,” he says. “The chemistry of making cement involves turning calcium carbonate into calcium oxide –– dropping two of the oxygen molecules by bonding them with carbon. So you literally have to make carbon dioxide to make cement. And if you want a hydro project or wind turbines or a pad for a solar farm, you need cement.”

It’s an often-overlooked example of the emissions that come from modern construction: no matter how much or how little carbon dioxide an energy technology will emit, you probably need to produce carbon dioxide to install it.

A PhD student in the University of Alberta’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, Miles is quick to point out these challenges of renewable energy –– even though he’s a staunch advocate for the energy transition. In the lab of Future Energy Systems Principal Investigator Pierre Mertiny, he works on a flywheel energy storage technology that could enable the implementation of renewables.

“Reliable storage could make intermittent energy technologies like solar and wind more useful for the home or safe for the grid,” he explains. “But that doesn’t change the fact that there’s no perfect technology, no technology that won’t somehow be responsible for some negative environmental impact in its life cycle.”

Miles believes acknowledging and addressing that reality is crucial to making the energy transition happen. He shares that perspective with countless other Future Energy Systems researchers, including four program-supported students who were with him this summer at the 2019 ABBY-Net School on Energy Transitions, hosted in Alberta’s Kananaskis Country.

For one week each year, the Albertan-Bavarian Research Network for Sustainable Energy Transitions –– ABBY-Net –– summer school brings together more than thirty students from Canadian and German Universities to tackle energy transition questions. The cement example cited by Miles was raised at this year’s school by Future Energy Systems researcher and University of Calgary professor Joule Bergerson.

“We can’t gloss over examples like the cement production,” Miles asserts. “And it’ll take people from all sorts of places and disciplines to make the transition work.”

Learning to communicate

Over the past year, Masters students Andrea Miller and Sonak Patel have spent a lot of time in front of crowds explaining the work being done in their Future Energy Systems project, led by Principal Investigator John Parkins.

The work includes the Canadian Renewable Energy Projects Map hosted on the Future Energy Systems website, reports surveying all renewable energy projects in Canada, and case studies analyzing community experiences with renewable energy. The audiences have ranged from conference-goers to administrators and policymakers to peers. Andrea and Sonak even helped open the 2019 FES Colloquium with a feature presentation.

But when they arrived at the ABBY-Net Summer School, neither of them knew fellow Future Energy Systems graduate students Miles Skinner or Natalia Vergara Bonilla. Andrea and Sonak are based in the Department of Resource Economics and Environmental Sociology, while Miles and Natalia are both in Mechanical Engineering. Despite similar goals and a common affiliation to Future Energy Systems, they had never met –– and that may be an indication of a long-term systemic problem.

“When we’re addressing complex energy questions, communication is one of our big challenges,” Andrea observes. “We need to be interdisciplinary –– integrating disciplines so that we can benefit from our mutual expertise. Right now I think we’re more multidisciplinary –– multiple disciplines in the same room, but not necessarily integrated.”

Sonak agrees, “When we were working on projects at the summer school, there were definitely times when the engineers would get into a conversation and I wouldn’t understand what they were saying.”

Having completed his undergraduate work in the University of Alberta’s Urban and Regional Planning Program, Sonak was accustomed to interacting with civil engineers, but technical terminology about energy technology was foreign to him.

“And I’m pretty sure I lost some of the engineers when I was talking about policy,” he adds. “This isn’t anyone’s fault, it’s the fact that our academic system has very clear boundaries, whereas energy transition is a problem that touches almost everything.”

Andrea agrees, “We need to think about ways to bring down these barriers, both internally and between us and the public. That probably means some sort of changes to the way we’re training our students. Programs like Future Energy Systems help by exposing different disciplines to each other.”

Different solutions, different contexts

Both Miles and Natalia strongly agree with Andrea and Sonak: more needs to be done to integrate different disciplines into energy transition research and planning. They saw firsthand how crucial the presence of planners, economists, and sociologists can be at the 2018 ABBY-Net Summer School, held in Bavaria.

“At that school we had a more technical group of students, whose focus was on the function of the system without social scientists present to offer a consideration of human behaviour,” Natalia explains.

Her own work is related to economics. Working under the supervision of mechanical engineering Professor Brian Fleck and Industrial Professor Tim Weis –– also the Executive Director of Electricity Research at the School of Business Centre for Applied Business Research in Energy and the Environment (CABREE) –– she is examining how the integration of wind into the Alberta marketplace could affect energy prices. This is an important topic because, according to the reports developed by Sonak and Andrea, Alberta is in the process of tripling its wind generation capacity.

“When you integrate an intermittent energy source like wind into your grid, the pricing for energy becomes more complex because demand and supply will not always align,” Natalia continues. “This is another complication of the energy transition that we need to acknowledge.”

Having social scientists like Andrea and Sonak at the 2019 school introduced new perspectives on those complications, raising questions about how human behaviour –– community support for or resistance to renewables –– could further complicate the market. Hailing from Mexico, Natalia was particularly interested in exploring those questions.

“In Canada, when we talk about social barriers to renewable energy infrastructure it is very different to what my country is experiencing,” she explains. “Economically and socially, the transition is going to have very different effects on some parts of the world, and without bringing together diverse expertise we will not be able to prepare properly –– or maybe even implement it at all.”

Janina Fuchs agrees. An undergraduate student in Geography at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, she is currently on a Mitacs-supported exchange at the University of Alberta, working with Sonak and Andrea to explore attitudes towards renewable energy in Canada. Attending ABBY-Net, she found fascinating differences between Canadian and German perspectives on the energy transition, clearly rooted in the countries’ different landscapes.

“Germany has twenty times the population of Alberta, and is half the size of the province, so our experiences and expectations about energy are very different,” she observes.

From Albertans’ habit of driving to remote locations in large vehicles, to the caterers’ offering of meat at every meal during the school, she found the choices made in the Canadian province very different to what she was accustomed to at home. She also found divides on proposed solutions.

“When students were asked whether wind turbines should be set up in the Banff area, all the German students were uniformly in favour. The Canadian students were not enthusiastic –– they cited concerns related to weather, wildlife habitat, and public uses that we simply would not have to consider in Germany,” she says.

“To me it reinforces that, even when we are all agreed on the principles, there will be different approaches in different contexts.”

In it together

Over the course of a week at the ABBY-Net summer school, all these different perspectives mixed and gelled. The participating students were eventually broken into groups to generate mock research funding proposals for projects addressing energy transition in Alberta. Andrea, Natalia, Sonak and Miles found themselves on different teams, and though each ultimately proposed a different sort of project –– everything from public education to a geothermal installation –– a common theme encompassed all four.

“Every single project hinged on having the social sciences and the natural sciences working together,” Miles says.

Sonak elaborates: “Each group had one or two engineers or scientists, a social scientist, a geographer, and a data researcher. The diversity was built into the team design, and the projects reflected that.”

“There was a mix of origins as well,” Andrea points out. “Students from German schools and Canadian schools.”

“And the students from those schools also originate from many countries,” Natalia adds.

This was a clear sign of the interdisciplinary direction future work on energy transition must take. As students worldwide recognize the necessity of looking beyond the traditional limits of their individual fields, research, discussion, policy, and action around energy systems will necessarily include a wide array of perspectives –– with diverse solutions to match.

By bringing students together from around the globe, the ABBY-Net summer school is helping establish networks that will enable these sorts of solutions for decades to come. Already, the network’s existence is forging connections –– if her supervisor had not been familiar with University of Alberta researchers through ABBY-Net, Janina would not have come to Canada on exchange.

“Germans and Canadians have a great opportunity to share strengths and partner with each other on energy,” she says.

Energy transition is a global challenge, and Future Energy Systems students are well-positioned to be part of the solution.

“I just don’t know who’s going to find an alternative to cement,” Miles concludes. “I mean, it’s literally the foundation of everything we do.”

For more stories about Future Energy Systems graduate students, click here.

To learn more about ABBY-Net, click here.