Bring back the bugs

Posted on

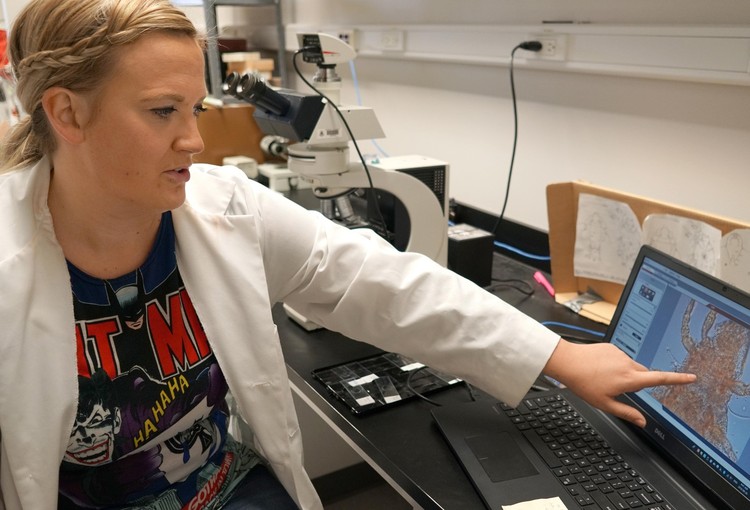

Future Energy Systems PhD Candidate Stephanie Chute-Ibsen at work in the lab identifying invertebrates.

Future Energy Systems PhD candidate Stephanie Chute-Ibsen is heading to Berlin to pitch a new perspective on land reclamation

Imagine a town has been wiped out by a natural disaster. The government hires contractors to rebuild the homes and businesses that have been lost, and a few years later gleaming new structures have risen from the ashes.

Government inspectors wander through the streets, count the number of new buildings and give the stamp of approval: the community is restored. Except the inspectors are alone on those streets. No one has moved back into these new buildings. It’s a ghost town.

Is the community truly restored if no one is living in it? If no one has come back, is the government using the right criteria to judge success?

Stephanie Chute-Ibsen (pronouns: they/them), a PhD candidate working with Dr. Anne Naeth in the Future Energy Systems Land and Water theme, is asking questions like those, but instead of a hypothetical community they're studying real sites being reclaimed after human-caused disruptions, and instead of counting families in houses they're counting tiny creatures that live beneath our feet.

Their idea recently captured the imagination of the UAlberta Falling Walls Lab jury, so this November they're bound for Berlin to spread awareness about invertebrates.

Introducing the Invertebrates

Insects, arachnids, and worms all fall into the category of invertebrates –– inverts to their friends –– and they’re a sensitive bunch. Though people often perceive ‘bugs’ to be omnipresent, these tiny creatures can be quite selective about the soils they choose to live in.

When they choose not to live in a certain area it could indicate that the living conditions are poor, and their absence could leave the site vulnerable. This is an important consideration when land is being reclaimed after disruptions –– particularly at sites like strip coal mines.

“We can replace the soil, add the right vegetation, and superficially the site can appear acceptable,” Stephanie explains. “But what we’re really concerned about is whether the ecosystem is healthy, stable, and resilient enough to withstand environmental pressures over time.”

Inverts have an important part to play in establishing that resilience because they have incredibly high diversity and play numerous functional roles. They contribute organic matter which affects soil fertility, aid in soil structure formation, and affect the availability of resources for other organisms including plants and microorganisms.

Without a functioning invert community invasive pests can move in, endangering the health of that site and even the surrounding ecosystems. Understanding invertebrate populations may be vital to successful land reclamation –– but it’s difficult to do.

To get started, you need to know a lot about invertebrates.

A Really Bad Roommate

Stephanie has been interested in bugs for as long as they can remember. Their home office hosts an extensive insect collection, many taken from the Edmonton river valley. They have pinned butterflies, beetles, and even a flea. The microscope they received at the age of 9 –– prior to moving to Canada from Germany –– has a place of honour in their living room.

Admittedly, their affinity for inverts unsettles some people.

“In undergrad I was a really bad roommate,” Stephanie laughs. “It was always fun trying to explain why I was rehydrating dead beetles on a rack next to the sink and that there was a container full of more samples next to the ice cubes in the freezer.”

But this passion, combined with a profound concern about the future of the environment, led them to take on the laborious challenge of studying invert populations at reclamation sites.

“The reason no one has done this before is because it’s a lot of work,” they admit. “Collecting the samples can be hard work, but I get to spend time outdoors which is always nice. The hard part is that when you get 400 mites out of a sample, you have to identify them one by one.”

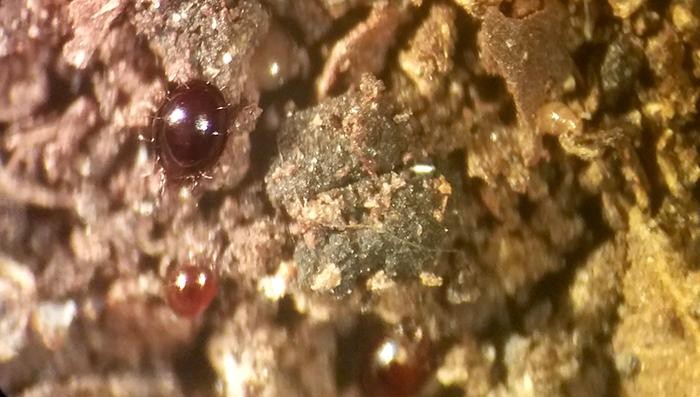

Tiny mites –– many barely visible to the naked eye –– are some of the most important indicators of soil health. When extracted from a soil sample, a few types are large enough to be categorized on sight, but most have to be made into slides so that their acarological family can be determined.

That meticulous, four-day process involves specially gluing them to a glass slide in a certain position so that specific features are visible, then curing them. After they’ve been prepared each one has to be checked under a microscope, and Stephanie is the only one on their team with the invert expertise to do the categorization. They recently enhanced that knowledge by attending the intensive, world-leading three-week Soil Acarology Summer Program at Ohio State University this summer.

“I absolutely love learning about mites, though you can definitely go bug-eyed,” they joke (they're an unapologetic lover of science puns).

Digging in

Stephanie is currently in their second year of collecting samples at the Westmoreland Coal Company Genesee Mine, 80 kilometers west of Edmonton.

“They take reclamation very seriously and have been so supportive,” they say. “We get access to our reclamation sites every month, and compare them with a nearby forested site that wasn’t disturbed by mining operations.”

To gather the inverts they use two methods: pitfall traps and litter and soil core samples containing live specimens. The pitfall traps are simple plastic deli containers placed in holes and left for one week, capturing all surface dwelling invertebrates.

The litter and soil core samples are taken to the Royal Alberta Museum. There Stephanie employs the Tullgren funnel extraction method, which uses light bulbs to gradually heat the samples from top to bottom, creating a temperature and moisture gradient. As the inverts within the sample migrate down to avoid baking, they’re collected for counting and categorization.

In addition to these samples, they assess the soil and vegetation, which allow them to see how the sites would be rated based on current conventional metrics of land reclamation. Returning to the metaphor of the rebuilt town, they're counting buildings while also conducting a census. The question is whether the buildings and the people correlate.

“Soil and vegetation parameters are the current reclamation metrics,” they explain. “We can look at a site and see how diverse and abundant the flora is, but if the soil health is poor, all of those plants could be far less resilient to climate shocks than undisturbed areas that look similar.”

If outside observers see a rebuilt town putting up skyscrapers, can they conclude that there are enough people to fill them? If the town had never been disturbed in the first place, it could be safe to assume enough people lived there to warrant the construction, but when an outside agent is responsible for construction, it’s more difficult to determine whether demand is balanced with supply.

“It’s possible that there is enough correlation –– that monitoring the soil and veg will give us a good indicator of the invert populations,” they concede. “But I’m betting there’s more going on in the soil than we know.”

They're willing to put in the effort to find out.

Inverts on the road

It will be a few years –– thousands of slides of mites –– before Stephanie can publish any conclusions about the importance of measuring invertebrates. If they do conclude that monitoring those populations is important, the finding will be the beginning of a lot more work.

“Many industries are taking land reclamation very seriously,” Stephanie says. ”With the climate changing and extreme weather events happening more regularly, we need to give them the best possible tools to know whether their reclamation investments are paying off.”

Those tools would include clear assessments of what invert populations are best suited to restore soil health, and what reclamation practices and techniques are likely to regenerate those populations.

Since the role of inverts in reclamation has rarely been studied, the list of things to learn is long –– but Stephanie doesn’t mind. Their plan is to become a Professor, carrying on with invert-related research and sharing their passion for the tiny creatures with new generations of students and the broader public.

They're off to a good start: at the University of Alberta’s fifth Falling Walls Lab, a qualifier for the international research competition that’s billed as a cross between a three-minute thesis and a TED Talk, their pitch ranked second out of the final fifteen –– bested only by a potential cure for cancer.

“It’s a little intimidating to be put up alongside someone doing that kind of work,” they say. “But soil is the very foundation of life, and without the invertebrates, we don’t have healthy soil.”

That’s the message they'll take with them to Germany, where they'll represent the University of Alberta and Future Energy Systems in the international Falling Walls competition.

“I am very excited to share my passion for the environment and to return to the wonderful country where I was lucky enough to grow up,” they conclude with a smile. “Bis bald Berlin.”

For more HQP profile stories, click here.

To learn more about Stephanie's project within Resilient Reclaimed Land and Water Systems, click here.

To subscribe for future stories, click here.